Dr. Aharon Maman’s interest in Hebrew began as a child in Morocco, when he first encountered the letters of the aleph-bet.

“I remember it was the eve of Shavuot when I was four years old. My uncle, Rabbi Avraham Hamou, may he rest in peace, wrote the letters of the aleph-bet on a board,

and smeared them with honey.

He made a whole ceremony out of it, and let me lick the honey off of the letters, so that the words of G-d’s Bible would be sweet in my mouth.”

Even today, this is a common practice in Jewish communities when the children start learning to read from the Bible.

Dr. Maman’s own roots reflect the languages he studies – he was born a Moroccan citizen, yet he retained the fiery, unquenchable core of the Hebraic Jew.

“The language of the conqueror ruled through the spoken word. Even so, Hebrew remained in the background, together with everything regarding the Jewish culture.”

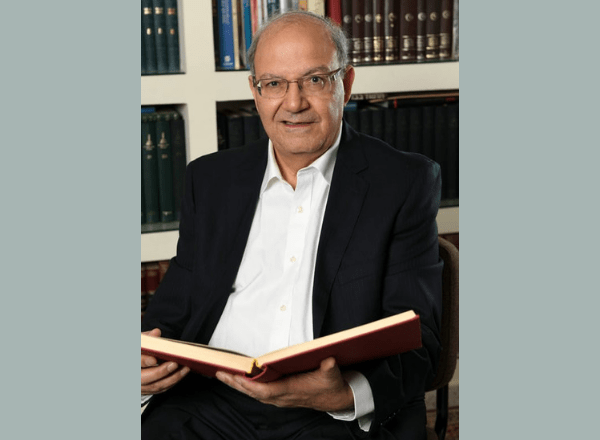

So says Dr. Aharon Maman, linguistics researcher, Israel Prize laureate, and founder of the Binyamin town of Psagot. From a young age, he nursed a tender love for the Land of Israel, and especially for the Hebrew word. Today, he serves on the faculty of the Hebrew University, in the Academy of Hebrew Language, and is globally one of the leading researchers of Hebraic languages.

“When I was growing up, I remember the moment my father was imprisoned in the wake of some Zionist activity which was forbidden in Morocco. After his release, my parents realized that the time had come to leave and to move to Israel.”

The Maman family moved to Kiryat Shmonah and later to Yavneh, and young Aharon acclimated to his new country in the vast plains of central Israel. He himself moved to Jerusalem, married, and chose to study in Hebrew University. He followed his passion, studying the Hebrew language, the same ancient letters that connected him to his roots as a young boy. In 1980, the volatile political climate worried Dr. Maman and his wife – they feared that Israel would lose the biblical heartlands of Judea and Samaria.

“I felt that I was not actualizing all the Zionist education I received from my home, and I wanted to give more. Thus, together with my family, I joined the foundation group which established Psagot 37 years ago. We were some of the first founders of the town. Psagot is a wonderful town, which overlooks Jerusalem and her surroundings. Its population consists of the finest people of Israeli society, which has among it scholars, and strengtheners of the Bible, and which is based in mutual responsibility.”

When you meet Dr. Aharon Maman, your first impression is one of a gentle grandfather with a jolly humour. Meet him in the halls of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, however, and you’ll find a fiercely intelligent researcher whose every fiber is dedicated to advancing the knowledge of Hebrew to ever greater heights. In recent years, he has won tremendous recognition for sleuthing out the ancient dictionary of the renowned medieval Jewish theologian, Rav Hai Gaon. This dictionary had been disposed of in the Geniza (a crypt for holy documents) of Fustat (old Cairo), Egypt. Many manuscript fragments were found in this famous storeroom in an Egyptian Synagogue.

“My romance with Rav Hai Gaon began thanks to my revered teacher, Professor David Téné…he gave me 6 photographs of genizah papers, which included 12 pages…it was an anagramic dictionary of Hebrew and Aramaic, whose definitions were written in Arabic…There are only 2 such dictionaries known to have ever existed. I had to determine whether this was a piece of one of them, or a third which had not yet been known in the literary world. I made great efforts to prove, beyond a doubt, that the pages were remains of the lost dictionary of Rav Hai…[Years later,] I searched for more remnants, among the collections of papers taken from the Cairo Geniza, which were scattered across some 70 libraries all over the globe. I discovered, in total, 52 leaves. Right now, I’m preparing them for publication.”

Dr. Maman’s fascination with Hebrew extends beyond the language itself, and back through the annals of time. He is currently pioneering research into the many individual Jewish languages of the Diaspora. He explains that although these languages mostly consist of the local native language, they carry a sort of linguistic DNA which encodes Hebrew. That Hebrew DNA was carried secretly in these languages from generation to generation, until Hebrew could be revived into a living language.

“The languages of the Jews in exile were created in an interesting way: each community adopted the local language, while adding to it a treasure of Hebraic words which weren’t encompassed by the local language…basically they used an invisible channel to pass down Hebrew from generation to generation, until we returned to full Hebraic speech in the 1900s. The miracle of the revival of the Hebrew speech in the modern era did not occur ex nihilo; rather, it functioned through this invisible channel, and of course through other channels – the Jewish liturgy and para-liturgy, and the creation of the written Hebrew. Together, they made it easy to renew the Hebraic speech, and to turn it into a language – for the future generations.”

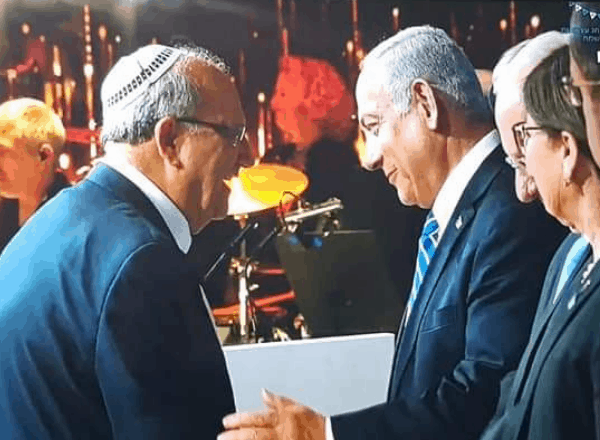

In recognition of his revolutionary studies of the Diaspora languages, Dr. Maman was recently awarded the 2019 Israel Prize. He says that when the Minister of Education Naftali Bennett phoned him to inform him of the honor, he was completely unprepared:

“I said to him ‘Minister, you should have told me to sit down on a chair. You could not have called at a more special time. Today is the 55th anniversary of our aliyah to the land!’ The minister became very excited, and the conversation was very emotional and special.”

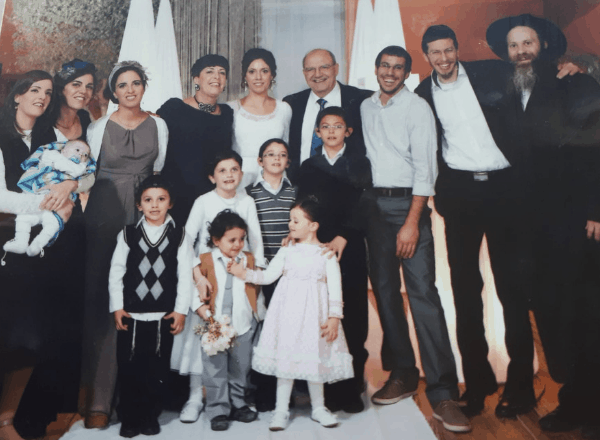

Today, Dr. Maman continues to develop his community of Psagot and his probing academic research, and to focus on the simple joys of life: his grandchildren.

“What do I dream of for the future? To see my grandchildren grow up in the way of wisdom, the Bible, and learning, and to complete the projects which I began many years ago.”

As though he turns the pages of time itself, Dr. Maman’s linguistic research reaches through the ages to something greater – back to a day when the Jewish people screamed out their seminal cry at Mount Sinai, “We will do, and we will hear!” (Exodus 24:7).

Despite all our trials since that day, despite being scattered across the globe like a page shredded and cast in the wind, despite everything, we have remained.

As G-d promised, “Like an eagle who rouses His nest, fluttering over His young. He extends His wings, He grasps them, He bears them on His wing.” (Deuteronomy 32:11-12)

This weekend (beginning on Saturday night, June 8), we will celebrate Shavuot, the holiday that commemorates the time when the entire Jewish nation stood at Mount Sinai and accepted the Bible and its commandments.

The unique power of Hebrew has shaped Jewish law, mysticism, and culture throughout our history. Generation after generation, we revere our language as one of the roots of our national identity.

Holding onto the words of the Bible is what preserved the Jewish people throughout exile.

“Hebrew already had enchanted me when I was yet a child…And the rest, as they say, is history.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]